This article, related to incorporating B149 code changes into daily operations, first appeared in the 2015 Nov/Dec edition of Propane Canada Magazine.

My last few articles have provided information and discussed the ramifications of the regulatory impact the 2015 editions of the fuels and pressure vessels codes and provincial regulations will have on the propane industry. I like to believe that one of the purposes of these articles is to provide information on the regulatory regime as it develops so that company owners and users of the relevant code and regulations can be proactive rather than being reactive to new requirements.

This got me to thinking that it is great to provide this information but what does a person do with it once they have received it? If the information ends with the reading of the article and no further steps are taken, then the regulatory impact will result in a non-compliant position subject to the legal means available for enforcement of the codes and regulations by the Authority Having Jurisdiction.

Knowledge

I learned long ago that knowledge, and the ability to translate that knowledge into workable solutions, is key to being proactive and keeping one step ahead of the game. I would, therefore, hope that my articles provide the trigger for readers to take the next steps.

Steps might include identifying areas requiring additional or new development of policies and procedures, as well as to identify training initiatives necessary for employees to continue to complete their tasks in an efficient, cost-effective, and safe manner.

Training Requirements

Training is very vital in any company or organization that aims at progressing. Training simply refers to the process of acquiring the essential skills required for a certain job. It targets specific goals, such as understanding a process or operating a certain machine or system.

It is common knowledge that a properly trained person becomes more informed about procedures for the various tasks he or she must complete and that the person’s confidence is also boosted by training and development. This confidence comes from the fact that the per-son is fully aware of his/her roles and responsibilities. It also helps the person to carry out the duties in a better way and even find new ideas to incorporate into the daily execution of duties.

Legalese Clauses

Regulations are written in what I describe as “legalese” which means that the lay-man’s clause wording developed and accepted by the working Technical Committees is reviewed and possibly edited by lawyers to ensure that the clause requirement meets the minimum standard required for enforcement by the Authorities Having Jurisdiction. This sometimes ends up with the clause not being quite as clear or concise as it was when the technical committee first developed the clause and therefore makes it difficult for the worker in the field to feel comfortable interpreting the requirement.

Regulations are written in what I describe as “legalese” which means that the lay-man’s clause wording developed and accepted by the working Technical Committees is reviewed and possibly edited by lawyers to ensure that the clause requirement meets the minimum standard required for enforcement by the Authorities Having Jurisdiction. This sometimes ends up with the clause not being quite as clear or concise as it was when the technical committee first developed the clause and therefore makes it difficult for the worker in the field to feel comfortable interpreting the requirement.

This is where the policies, procedures, and training come into play by ensuring, whether a person is a technician, fuel delivery person or plant operator, that each person in that position gains similar skills and knowledge. This brings each position to a higher uniform level, making the workforce more reliable in completing the task correctly the first time.

More Than Having a New Code

When one understands the requirements for uniform regulatory knowledge, the legalese of the written clauses, and the need for new technical knowledge, the need for effective training becomes evident. The training of technicians, fuel delivery personnel and plant operators is just not as simple as giving those persons a copy of the latest code and provincial regulations.

Recap of 2015 Regulatory Impact

While there have been numerous changes within the 2015 code editions, there are three primary regulatory initiatives which will require propane company owners and users of the codes and regulations to develop and/or edit existing policies and procedures. These changes will also require training of staff to ensure they can correctly complete the tasks required for the company to meet its regulatory compliance obligations for 2016 forward.

(1) Pressure Relief Valve (PRV) Change Out

As previously stated in my May/June 2015 article on this subject, it is my opinion that this requirement is most likely going to be the most challenging regulatory requirement the propane industry has faced in its history. This single requirement will put a tremendous strain on the industry’s resources, people, equipment, and finances.

Even before there is any field activity on the replacement of PRVs it is essential the company have in place the necessary policies and procedures and trained staff to perform the actual field work.

The task of replacing PRVs is not as straightforward as it sounds and can be-come quite complicated and complex when you have to consider the logistics of:

- keeping customers supplied with propane;

- exchanging the customer’s propane tank (which could require evacuation of the product on-site);

- dealing with tank components which may not operate as designed or are not available to evacuate the pro-pane from the tank;

- transporting tanks from the plant to the customer site and then back to the plant;

- evacuation of the propane from the tank at the plant; and finally

- replacing the PRV.

This means that companies should already be diligently working on developing their policies and procedures, identifying relevant training programs, and scheduling the training of technicians, helpers, and bulk truck drivers as soon as possible.

(2) Construction Site Cylinder Storage and Use

There are extensive new requirements that affect how propane cylinders are stored and used on construction sites. As with the PRV change out, companies will be required to provide new/edited policies and procedures and additional training for cylinder delivery personnel.

There are extensive new requirements that affect how propane cylinders are stored and used on construction sites. As with the PRV change out, companies will be required to provide new/edited policies and procedures and additional training for cylinder delivery personnel.

Several provinces and territories automatically adopt the latest edition of the code once it is published. For example, the B149.2 Propane Storage and Handling Code was published by CSA in Au-gust 2015. Provinces and territories that have not already adopted the 2015 code will be doing so in 2016. This means that some delivery personnel delivering to construction sites for the 2015/2016 winter construction heating season must be trained in the new requirements. In addition, the company must have in place policies and procedures describing how the Company will deliver propane cylinders to the construction site.

(3) New Propane Facility Maintenance Requirements

The purpose of the new clauses in the code is to provide a minimum standard for the operation and maintenance of propane facilities and equipment. The new clauses apply to tank systems, filling plants, container refill centres and other facilities where liquid propane is piped to a vaporizer or process. Because there are many variables, it is not possible for the Code to prescribe a set of operation and maintenance procedures that will be adequate from the standpoint of safety in all cases without being burdensome and, in some cases, impractical. The proposed clauses establish a baseline or minimum standard.

The maintenance procedures are to cover testing, inspection, monitoring, and documenting of the equipment, its repair, and general upkeep.

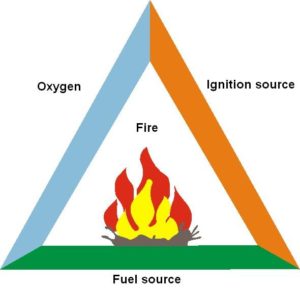

There is also a requirement for persons who perform maintenance on facility propane systems to be trained in the hazards of the system and in the maintenance and testing procedures applicable to the facility.

Once again, this requirement is already in place in some provinces and territories and will be coming into force 2016 in those provinces and territories that do not automatically adopt the latest edition of the code.

These new requirements will require some companies to develop new policies and procedures with respect to maintenance of the propane facilities described and others to edit the policies and procedures to address the new requirements. Also, the training component is new within the code and therefore will require the identification of relevant training programs and the scheduling of personnel to take the training.

In Conclusion

It is my hope that this article will be the catalyst for the reader to become proactive and to take the next necessary steps to ensure that his or her company develops the policies and procedures, identifies the training initiatives required, and schedules the training of staff to meet the new regulatory obligations.

The Fuels Learning Centre has developed an extensive training program covering all of the aspects listed above for evacuating propane tanks regardless of location and the change out of the PRV. The course is currently being studied by several Authorities Having Jurisdiction across Canada for their review and comment, as is the process for all new courses related to regulated activities. It is anticipated this course will be available for our Instructors to conduct training on or be-fore January 1, 2016.

Also, we have developed a new course to address the requirement for persons who perform maintenance on propane facility systems to be trained in the hazards of the system and in the maintenance and testing procedures applicable to the facility. We expect this course to be available for our Instructors on or before January 1, 2016, as well.

Our training courses for cylinder delivery and installation of construction heaters already provide the 2015 code requirements your staff and customers will require in order to complete their duties and keep the company in compliance for the 2015/2016 winter construction heating season.